from a little series we took as a birthday gift to my mother

If I were a photographer, I would do a whole study of children with books. During my senior year, my college hosted a show of Abelardo Morell’s photographs of books. I was ensorcelled. I’ve appreciated books all my life, first as vessels of story, later also as objects with their own beauty, but under Morell’s lens they become landscapes, new worlds taking physical as well as figurative form. (Appropriately, he illustrated Alice in Wonderland in 1998.)

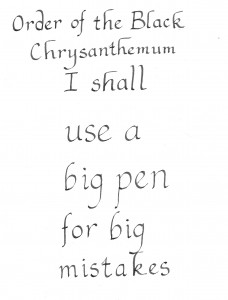

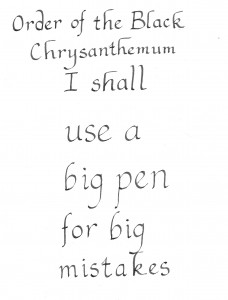

I’ve been thinking about the beauty of the form magnifying the beauty of the content since I visited the Lloyd Reynolds retrospective exhibit at Reed College last week. (Alas, it has closed, so you can’t go see it now.) I had the chance to go with our fourth and fifth graders, who have been studying the arc of human achievement across the millennia, from the ancient constructions through the Renaissance, and have learned both calligraphy and typesetting. Lloyd Reynolds was internationally known as a great calligrapher and teacher of calligraphy; he also designed books and carved woodblocks and Punch and Judy puppets. He influenced pretty much everyone practicing calligraphy in the Northwest today and can even be credited with the existence of decent type faces for the computer, thanks to his sway over students like Steve Jobs (who dropped in on Lloyd’s classes after he dropped out of Reed) and Sumner Stone. The kids and their teachers and I admired scores of his hand-lettered signs, weathergrams, favorite verses and quotations, and diagrams of pleasing page formats and relationships between letters. Later we got to try our own hands at some calligraphy, and I was struck by Lloyd’s advice to his students:

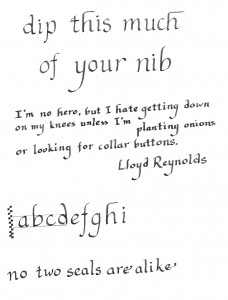

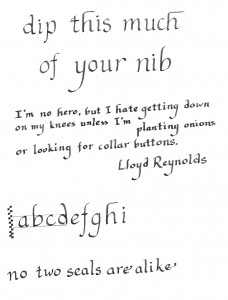

The Order of the Black Chrysanthemum was his tongue-in-cheek name for the brotherhood of calligraphers, who could always be identified by the generous ink blots on their shirts, should they absent-mindedly place their pens in their breast pockets. And he wanted aspiring calligraphers always to use large pens so that their mistakes would be loud, proud, and easy to spy. Then they could do better the next time. I love this. It’s entirely counter to my own penchant for fastidious workmanship, but too often those efforts wind up crabbed and I never get the flow. My pen was not nearly large enough for my mistakes on this day, as you can see from my unlovely samples here, but I thoroughly enjoyed myself and have been seized by a desire to take a calligraphy class and to read the work of Edward Johnston, which Lloyd wrote was “a lightning bolt” for him when he studied design. I also wish there were a biography of Lloyd himself. One case in the gallery was devoted to ephemera from his investigation by the House Un-American Activities Committee; he refused the summons to testify and I found his words on the subject deeply satisfying: “I’m no hero, but I hate to get down on my knees unless I’m planting onions or looking for collar buttons.” They put me in mind of E.B. White.

The Order of the Black Chrysanthemum was his tongue-in-cheek name for the brotherhood of calligraphers, who could always be identified by the generous ink blots on their shirts, should they absent-mindedly place their pens in their breast pockets. And he wanted aspiring calligraphers always to use large pens so that their mistakes would be loud, proud, and easy to spy. Then they could do better the next time. I love this. It’s entirely counter to my own penchant for fastidious workmanship, but too often those efforts wind up crabbed and I never get the flow. My pen was not nearly large enough for my mistakes on this day, as you can see from my unlovely samples here, but I thoroughly enjoyed myself and have been seized by a desire to take a calligraphy class and to read the work of Edward Johnston, which Lloyd wrote was “a lightning bolt” for him when he studied design. I also wish there were a biography of Lloyd himself. One case in the gallery was devoted to ephemera from his investigation by the House Un-American Activities Committee; he refused the summons to testify and I found his words on the subject deeply satisfying: “I’m no hero, but I hate to get down on my knees unless I’m planting onions or looking for collar buttons.” They put me in mind of E.B. White.

After we’d done some practice sheets (the kids wrote out the Shakespeare quotations they’d memorized), each of us penned a weathergram — a poem of only about ten words written on a strip of paper from a grocery bag and hung outdoors to weather — and found a home for it on Reed’s grounds. There was lunch and a merry game of Capture the Flag, girls against boys. I only played defense because, although I am old and out of shape in comparison to your average healthy ten-year-old, I have much longer legs. But I made those boys think twice about an assault on our pile of cones. It was bliss.

Even better was the chance afterward to peek into the Special Collections library, a treasure trove of ancient books — Ptolemy, Pliny, antiphonaries, bestiaries, Isaac Newton — and beautiful art books of more recent vintage. The children had to hold the elevator for the adults who couldn’t tear themselves away at the end.

I returned to my usual job, which currently consists of wresting an algebra book out of InDesign —a program I am totally unqualified to use — and wished I could be spending this much time hand-lettering the darn thing or setting it in metal type. It feels ironic that, at a school so heartily devoted to making things by hand, I’ve got the job of translating it all for the outside world via computer. (Nobody senses this irony better than my husband, who knows just how limited my competence with computers actually is.)

I find myself longing for Ada to be a few years older so that she and I can make things together. I don’t want to rush these sweet baby days of wonder and discovery, but I picture setting up a scriptorium in the living room bay and the two of us crafting hand-lettered books. Right now my future calligrapher is screaming about the indignity of nap time and gnashing her stuffed otter with her gums in frustration, so we have a little way to go. I’d better go read her a book. One step at a time.

Oh, and my favorite thing from the Reynolds exhibit, a tiny woodblock print only an inch and a half wide: