Translation

Lately I have been opening boxes. In a strange convergence of family moves seven years ago, a surprising number of my ancestors came to live in my house just as I was buying it from my aunt. My great great grandparents gaze mildly down from their gilt frames in the living room, apparently serene about the move from their brownstone in Gilded Age Manhattan. Great Aunt Priscilla watches over my daughter’s bedroom from her faded pencil portrait, her wide blue eyes and little mouth reminding me of my son. Here are my grandmother’s purple chairs and here her needlework, here her desk and here her Shaker broom, and there on the mantle the giant sugar pine cones she brought home from a trip to California long ago. On the shelf below are a few of the dishes a world-traveling great grandfather collected in China. It’s cozy in here with all these generations crowded together. And there is far more family residue still to sort, still in the brown boxes stamped Arnoff Moving & Storage.

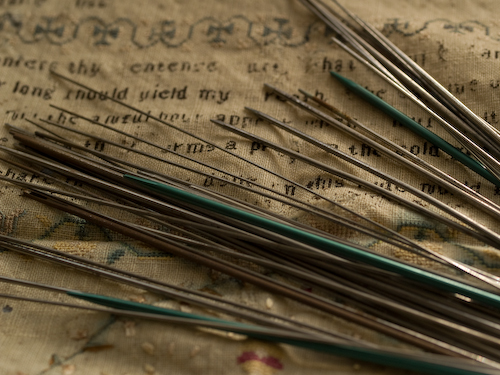

One large carton contains the innards of Granny’s desk, which spanned a whole room with large windows from which she could watch the cardinals and wild turkeys and chipmunks and all the creatures of the Connecticut woods about their business in the leaf litter. There are large boxes of “boilfast” thread (I tested each wooden spool to winnow out the rotten ones and take them to my children’s school, where they’ll be put to creative use) and assorted buttons (I smiled at the good—cunning tiny badminton birdies carved of wood—and frowned at the bad: large handmade pink ceramic freeform shapes that strongly resemble feminine anatomy I shan’t mention on the internet). There is an ivory mechanical pencil printed “On To Alaska With Buchanan;” Professor Google tells me a Detroit coal merchant named George Buchanan led expeditions of young people up north between 1923 and 1938…was my grandfather one of those adventurers? There are ancient knitting pins—and I use the old term because pins they are. My modern needle gauges haven’t enough zeros to tell you just how fine they are. About the diameter of a standard paper clip, some of them. And folded into a stack of fabric squares was a girl’s needlework sampler. From 1796.

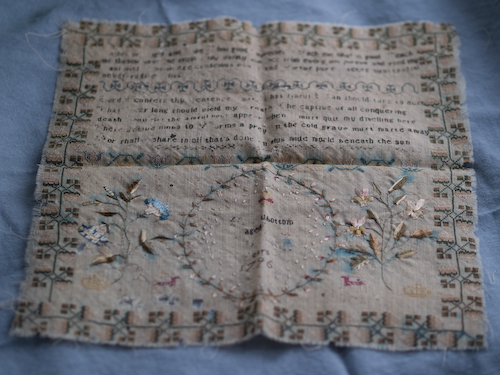

What does one do with such a treasure? It’s in poor shape, full of holes and bleed marks (the green dyes must have been particularly difficult to fix), badly faded on the front side, with much of the text simple vanished where the black thread has disintegrated. The most tantalizing details, the girl’s name and her age, are lost forever. Miss -bottom, we’ll have to call her, which isn’t a very dignified moniker for an artist. But the year stands proud. 1796. Twenty years after the Declaration of Independence. (But is this sampler even American? Granny’s family was half English, so perhaps not. And would an American girl have stitched crowns on her sampler? Someone out there probably knows enough about the iconography of the time and the needle arts to tell me.) I don’t know how to begin to preserve this piece of history… clearly not folded in quarters, but I daren’t even try to iron it out now.

At some point the little wheels began to turn in my mind. When I was at Bowdoin College I encountered the photography of Abelardo Morell. At the time he was working with books and maps as his subjects. I was hooked. Seriously, go click through his gallery. I’ll wait. Don’t miss this one near the end.

And now I’ve started to wonder if there might be way to translate this venerable piecework into another medium. Sadly, I don’t have Morell’s skills with a camera. But when I turned my lens to these threads and looked closely, I found fairy tale beasts…

… and allegories: beware, little girl. The fabric is frayed. You are standing at the raveled edge.

There is something so touching about the human imperative to impose beauty and order on an uncertain and often brutal life. The verses this girl chose, stitching each letter so neatly and minutely, framing them with a fretwork of flowering vines and an exuberance of embroidered blossoms… I looked them up, relying on the salient phrases I could decipher to lead me to the origin.

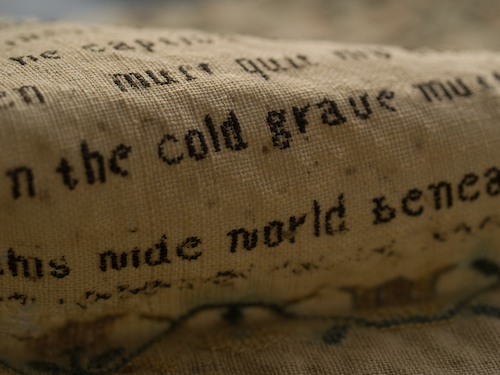

“LORD, I confess thy sentence just, That sinful man should turn to dust; That I e’er long should yield my breath, The captive of all conqu’ring death. Soon will the awful hour appear, When I must quit my dwelling here: These active limbs, to worms a prey, in the cold grave must waste away; Nor shall I share in all that’s done, in this wide world beneath the sun.”  –The Works of Philip Doddridge, Volume 5, Lesson XXI, On death

In 1796, how many people had this child already lost? How many playmates dead of fever, how many aunts or cousins in childbed, perhaps her own brother or sister tucked in the earth after accident or illness? It grieves me to think of someone her age calmly (and, it must be said, with a fine eye for typography) working those resigned phrases, feeling their weight as she must have done. And yet I have to admire her gumption in juxtaposing those somber reflections with that fanciful botany. The other passage she chose was from James Thomson’s 1726 poem “Winter:”

“Father of Light and Life! thou Good Supreme! / O teach me what is good! teach me thyself! / Save me from folly, vanity, and vice, / From every low pursuit! and feed my soul / With knowledge, conscious peace, and virtue pure; / Sacred, substantial, never fading bliss!”

(Our Miss -bottom sensibly reigned in the punctuation.) Knowledge, conscious peace, morning glories, and exquisite little red deer against the cold grave. Wise child. I will treasure your tiny stitches.

Posted: February 2nd, 2013 at 4:55 pm

What an amazing treasure; I found a similar heirloom in my mother s house and I donated it to Lincoln Cathedral in England. I love to look at things like this made by little hands that have long since turned to dust. I get the feeling we are all in this together somehow.

Are you going to take it to a restorer – I think I might if it were mine.

The knitting needles remind me of the lengths of scrap wire that small children in the u.k. used to knit fair isle and guernsey sweaters.

Posted: February 3rd, 2013 at 7:26 am

Wow! Incredible that your family has preserved this treasure for so many years and now you become it’s steward. I’d call in a professional, it’s so precious. Thank you for sharing it with us but the best part, as always, are your musings.

Posted: February 3rd, 2013 at 7:53 am

The sampler is worth a small fortune. Please treat with care and find someone to help you conserve it. Yes, they did stitch crowns into their needlework as a symbol of heaven. All the other stitched icons have meaning, too. You have an amazing piece of woman’s history in your hands.

Posted: February 3rd, 2013 at 7:57 am

Lovely post, lovely pictures. HiyaHiya makes a needle gauge that goes down to 6-0. (I knit sweaters for my Asian Ball Jointed Dolls; I am all too familiar with 6-0 [000000] needles.)

Posted: February 3rd, 2013 at 9:31 am

I’m going to pass this along to my MIL. She has several connections in the textile preservation world. I’ll see if she has any thoughts. It’s beautiful!

Posted: February 3rd, 2013 at 12:29 pm

Contact the nearest museum with a good textiles collection and ask them about what can be done to stabilise/preserve it. They should also be able to tell you more about it. What a find! It is beautiful.

Posted: February 3rd, 2013 at 12:48 pm

That is such an amazing piece. I hope you are able to find someone to help you restore and preserve it.

Posted: February 3rd, 2013 at 7:23 pm

There’s a blogger (http://needleprint.blogspot.com.br/) who posts a lot about old samplers. Maybe she could help with yours?

Posted: February 3rd, 2013 at 7:39 pm

Unspeakable treasure. And you’ve done it tremendous justice already in the writing of this piece. I love how you describe taking to it with your camera and really starting to see it. It does force you to really peer at stuff and see objects differently some times.

Please write again if you have success in following up conservation work with it!

Posted: February 3rd, 2013 at 10:19 pm

Hi! I’m MIL to Tracy (#5). It really is a treasure and you are commended to give it such respect. If you intend to keep it, don’t do anything, even iron, until you’ve contacted The American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC). That can get expensive. You might look for a reputable history or textile museum near Granny’s home or yours. If they accept it, they’ll conserve it. If they don’t, they may refer you to another collection. If you decide to keep it, research all you can (family heirloom?), both provenance and care. Stabilize it, rather than repair, find an appropriate display, and enjoy!

Posted: February 3rd, 2013 at 11:36 pm

What an amazing find. I feel like I might be coming down with a new obsession. Is that clover along the edges and between the verses? Professor Google informs me that “Clover is a symbol for the trinity because of the three leaves attached to each stem. It is said that St. Patrick used the clover to explain the trinity in his early preaching and it has since been associated with this saint.”

Posted: February 4th, 2013 at 11:15 am

Thanks for that resource, Suzanne! Looks like there is a woman in Beaverton who could look at it for me.

Posted: February 4th, 2013 at 12:53 pm

Beautiful. Even my reproduction samplers don’t look half as dainty as this wonderful piece.

Posted: February 4th, 2013 at 1:20 pm

It is indeed a treasure, Sarah. and the blogpost you have written about its journey to you and your becoming entranced by it is also a treasure. Thank you so much for sharing this precious bit of your family’s history. Good luck in finding a competent restorer to help, if you decide to keep it, or a suitable museum that will preserve it. And do keep us all posted on what happens next.

Posted: February 5th, 2013 at 3:20 pm

What a treasure, perplexing though it may be to know how to care for it. I love the idea of translating it into some other art, your handiwork. You’ve already done a fine job with your photos and words.

Posted: February 5th, 2013 at 5:20 pm

The lovely sampler is a treasure and you have already paid tribute to the artist by recognizing it’s beauty. Besides consulting with a textile preservationist, I’d consider reproducing some motifs and creating your own sampler as a tribute to the unknown woman. Your post is beautifully written.